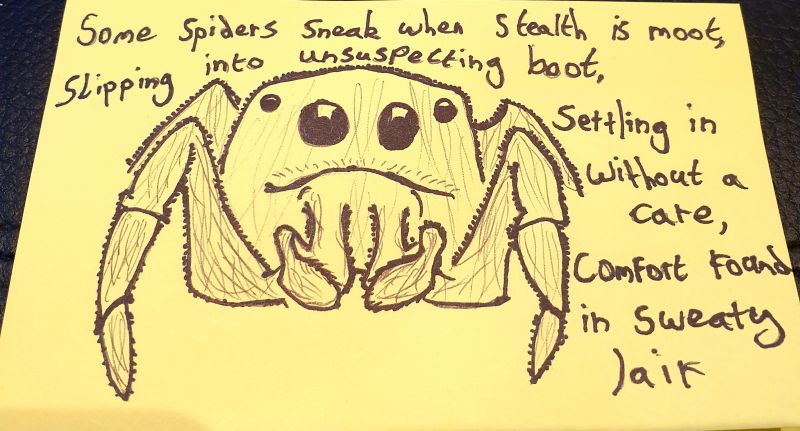

Some spiders sneak when stealth is moot,

Slipping into unsuspecting boot,

Settling in without a care,

Comfort found in sweaty lair

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Please be mindful that, while episode 81 of the Magnus Archives, “A Guest for Mr. Spider,” is the focus of this article, I may reference specific events or information from later episodes in passing. This is not a spoiler-free zone, apologies!

I will gamely admit that I currently view all creative works I encounter through a Magnus Archives conversion lens, as I’ve spent the last three months thoroughly marinating myself in all existing episodes and as much sweet, sweet fan-created content as I can get my greedy little hands on.[1] My obsession also means that I’m spotting connections and parallels to the show’s motifs everywhere, including innocent bystander blog posts that turn up on WordPress Reader. Which is where I spotted Dim But Bright Poetry‘s charmingly illustrated “Spider Sense,” now featured at the top of this post. Almost immediately after reading it I thought of “A Guest for Mr. Spider,” and could not stop thinking about it.

A quick note before I get started: spiders in the Magnusverse serve several specific narrative functions, and I have every intention of giving discussing these functions and plotty labyrinths in more detail at a later date–but, I’m not going to get into them in detail today. Today I just want to write about spiders, I guess.

Art by lunarsmith on DeviantArt

Is there enough collective cultural knowledge behind the verse, “along came a spider,” to transform it into a literary conceit? I think there must be, otherwise spiders and their webs and the sorts of spidery characters who crouch at their centres–or find themselves tangled up within them–wouldn’t be such a mainstay of literature. Specifically children’s literature, where the spider as a character is nearly always sly and clever and unambiguously up to no good, and therefore a reliable source of dramatic tension in a story or poem. When the spider comes along in a children’s tale, its arrival signals to a young reader that someone in the story is in danger, whether that someone is Mary Howitt’s Fly or, as is probably the case in “Spider Sense,” some unknown person’s socked foot. (Or the spider itself. One small spider vs. one large foot? Odds aren’t looking good for you, little spider.)

This brings us to The Magnus Archives, an audio drama horror podcast produced by The Rusty Quill that is intended for older audiences and so lacks on its surface anything to do with children’s literature. But Episode 81 is transparently about childhood, grounded in the recollection of narrator and central protagonist Jonathan Sims’ childhood trauma as he records his statement for the Magnus Institute.[2]

The object at the centre of his trauma is a book–a children’s book, at first blush–called “A Guest for Mr. Spider.” And this book, more than any of the other nightmarish tomes in the series–which are all capable of scarring minds, ruining lives, and dispensing horror after horror upon anyone unlucky enough to stumble upon one–is the one book that feels the most fundamentally evil to me as a listener. I suspect it feels that way because it is the only one whose very design preys upon the trust of children and their engagement with stories.

“Will you walk into my parlour?”

(Time to don my dusty old literature academic’s cap; it’s a bit out-of-date, I imagine, since the last time it saw any real use was the mid-00’s, but I might as well put that literature degree to some use.)

Storytelling is a marvellously useful tool for imparting morals and wisdom onto children, however dubious the quality of the morals or wisdom in question may be, and for as long as stories have been used in teaching, spiders have made appearances in the lessons. Those morality lessons and cautionary tales helped develop the foundation of the Spiders Are Scary trope, which now does much of the heavy lifting for content creators and content consumers of all ages. The trope makes the spider an easy object for any author or storyteller to decorate with ominous or undesirable traits as filigree, to warn the reader that danger is coming. Crucially, the story as a childhood experience itself, with clearly defined boundaries (by parents, caretakers or teachers, hopefully) between what is real and what is not real, allows children to experience the apprehension and fright of encountering the spider-as-storybook-villain from a place of safety, while ostensibly absorbing whatever message their instructors wish to impress upon them.

Example: many spider species hunt via entrapment of their prey; this creates a useful parallel for caretakers to teach children about the importance of being mindful of their surroundings and wary of strangers, lest they wander into the web of a different kind of monster.

Obviously there is fertile ground here for the spider archetype to be exploited in literature, so that children learn to fear “othered” groups who are statistically more likely to be the victims of predation rather than perpetrators of it themselves (e.g., immigrants, people of colour, my very own queer community, etc.), and unpacking that misuse requires and deserves a post of its own. So, for our purposes today, it is the established and expected relationship between fear of, and safety from, the story itself that I’ll focus on to guide my discussion. Because it is that expected relationship which makes listening to and telling scary stories such a commonly shared experience among children–and which makes its deception of its readers so insidious.

As a former[3] child myself I believe I can say with some authority that there is very little a child enjoys as much as building up a battery of terrifying tales to spook their friends with at their next slumber party–besides the actual act of telling the tale and watching their friends clutch at their blankets in fear, of course. Toss a rock (gently) into any group of kids, and the odds that you’ll bonk someone on the head who has a fear of spiders is high enough to make scary spider stories a required component of any such literary arsenal. In short: want to increase the odds of giving your friends a real fright? Tell a scary spider story.

And it works. But more importantly, it’s fun–both the listening and the telling.

Because as scared as you might be at the time, you know deep down that no matter what Becky says about what may have happened when she and her cousin played “Bloody Mary” together over fall break, what happens in the story stays in the story. Those are the rules of engagement: you choose when you wish to be frightened, and you choose when you are done. In the real world, which you inhabit and the story does not, you can put the story away when you are finished with it, and then a spider is just a spider again. What little danger might exist (e.g., you get a bit more of a fright than you bargained for) passes when the story ends, and you’ve had the time to gather up the threads of your imagination and stop startling at the sight of your own shadow.

It’s the necessary come-down all of us are familiar with after immersing ourselves in a good scary story: you are you–not Mary Howitt’s Fly, nor the girl from Alvin Schwartz’s The Red Spot, nor even the soul unlucky enough to stick their foot in the boot in “Spider Sense.” You are you, and the spider is just a spider, with no hidden motives or desires, and it will never seek you out to harm you because of some inherently evil quality spiders possess. You are you, a real person in the real world, and the fictional characters that frightened and delighted you will be waiting for you when you next want to return to that story. But for now, you have chosen to walk away from the parlour, and closed the door behind you. You are safe.

And that childlike presumption of safety from the story itself is what makes “A Guest for Mr. Spider” such a cunning and evil artefact within the world of The Magnus Archives, as well as a viscerally effective stand-alone piece of horror fiction. Because those time-honoured rules of engagement between the story and the reader are now carefully articulated threads in Mr. Spider’s web, and each page in the book that you turn takes you closer and closer to the predator at its centre.

To borrow a quote from William Friedkin (who, to be candid, I first heard quoted on Pseudopod by host and Peter Lukas voice actor, Alasdair Stuart), “True horror is seeing something approach.” In “A Guest for Mr. Spider,” true horror is seeing an isolated, lonely child approach something unspeakably horrible, and being unable to stop it, or look away.

Thanks for reading! This post is part one of a two-part series discussing spiders as a literary device in “A Guest for Mr. Spider.”

[1] If you’re a fan of the show, I’ve included links to some of my favourite fanworks at the bottom of the post. Episode numbers are included so you can avoid spoilers.

[2] It’s debatable whether these statements are really for the Institute at this point anymore, but that’s another matter for another time.

[3] Citation absolutely needed.

The Magnus Archives recommended fan content

- “Statement of Detective Alice ‘Daisy’ Tonner,” b&w illustration of episode 61 by tumblr user tenthousandbees-art

- “The Magnus Archives Animatic – Episode 91: The Coming Storm,” incredible 3 minute animation with podcast overlay by Erin Stewart